The Oil and Gas Addendum

The Centerline Presumption – Who Really Owns the Oil and Gas Under Roads and Highways? (Part II)

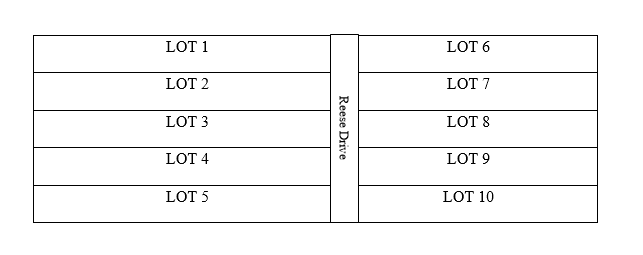

A troubling and confusing issue here in Pennsylvania concerns the ownership of oil and gas rights under roads and highways. For example, let’s assume Farmer Joe owned 115 acres in Greene County. In 1981, Farmer Joe sells the 115 acres to a developer called XYZ Development. As part of its plan to develop the 115 acres, XYZ Development dedicates a public roadway through the proposed development known as “Reese Drive”. The township thereafter accepts the dedication and Reese Drive is subsequently graded and paved. Reese Drive runs in a north/south direction through the center of the 115 acre parcel. In 1984, XYZ Development subdivides the 115 acres into ten (10) smaller lots on either side of Reese Drive. Each lot fronts approximately 400 feet on Reese Drive as depicted below:

Over the years, some of the lots are developed with houses and others simply remain vacant. The deeds from XYZ Development to the individual lot owners i) do not reserve or except the oil and gas under each individual lot and ii) all reference Reese Drive as a boundary.

In 1990, your father purchases Lot 3 and Lot 4 from XYZ Development and builds a house on Lot 3. In 2023, you sign an oil and gas lease with ABC Production for Lot 3 and Lot 4, which you assume includes a portion of the acreage located under Reese Drive (i.e. from the eastern edge of Lot 3 and Lot 4 to the center of Reese Drive). Shortly thereafter you start to receive production royalties from ABC Production but the royalty calculation excludes the acreage under Reese Drive. ABC Production informs you that XYZ Development is claiming ownership of the oil and gas underlying Reese Drive. You are angry, frustrated and confused – how can XYZ Development have any claim to the oil and gas under Reese Drive?

For many years, a doctrine known as the “centerline presumption” suggested that when your father purchased Lots 3 and 4, he also acquired the land (and the underlying oil and gas) to the center of Reese Drive. That may no longer be true. As we have written before, confirming the ownership of oil and gas under roads and highways is complex and can be confusing. See, The Strip and Gore Doctrine – Who Really Owns the Oil and Gas Under Roads and Highways? (July 2023). Recently, the Colorado Supreme Court heard oral argument on this evolving issue. A decision is expected in the Great Northern Properties LLP v. Extraction Oil & Gas appeal later this spring. As detailed below, landowners and drilling alike should closely monitor the Great Northern Properties appeal as it could impact how we analyze such tittle issues here in Pennsylvania.

At issue in Great Northern Properties was a road known as West Eleventh Street (“Eleventh Street”) located in Greeley, Colorado. In March 1974 and November 1975, the developer sold three parcels abutting Eleventh Street to three different buyers. The deeds conveying these parcels did not reserve or except any oil and gas rights (the “Source Deeds”). Each of the Source Deeds did, however, reference Eleventh Street as a boundary.

In January 2019, the developer sold the oil and gas rights underlying Eleventh Street to Great Northern Properties, LLP (“GNP”). Prior to this time, Extraction Oil and Gas, Inc. (“Extraction”) had entered into oil and gas leases with the owners of the abutting parcels. GNP disputed and contested the validity of those leases and filed a quiet tittle action in the winter of 2019.

Extraction defended the suit based upon the so-called “centerline presumption.” Extraction argued that, by application of the centerline presumption, the Source Deeds conveyed not only the abutting parcels themselves but also a fee interest to the center of Eleventh Street, including the oil and gas estate. In essence, Extraction suggested that the centerline presumption operated to convey both the surface and the oil and gas estate underlying Eleventh Street. GNP disputed this contention and noted that such a ruling would constitute an unwarranted and dangerous expansion of the centerline presumption. In GNP’s view, the centerline presumption only applies to the surface estate underlying the roadway and, therefore, no oil and gas interests were conveyed by the Source Deeds.

The trial court agreed with Extraction and ruled that the developer “conveyed the mineral interest to the centerline of the roadway. . .” As such, the trial court denied GNP’s quiet title action and entered judgment in favor of Extraction and the abutting parcel owners. GNP then appealed to the Colorado Court of Appeals.

Before we address the Court of Appeals opinion, a brief primer on the centerline presumption is warranted. The presumption generally provides that when a grantor conveys land abutting a road or highway, the grantor intends to convey title to the center of that road or highway. In Rahn v. Hess, 378 Pa. 204 (Pa. 1954), the Pennsylvania Supreme Court recognized the presumption and opined:

“[I]t is settled law in Pennsylvania that where the side of a street is called for as a boundary in a deed, the grantee takes title to the center of it, if the grantor had title to that extent, and did not expressly or by clear implication reserve it. . .”

See also, Ferko v. Spisak, 541 A.2d 327 (Pa. Super. 1988) (“[S]ince the eastern side of Franklin Street was called for as the Ferko’s western boundary, Rahn directs the conclusion that title to the center of Franklin Street passed to the Ferkos. . .”); Asmussen v. U.S., 304 P.2d 552 (Col. 2013) (“. . . the conveyance of land abutting a highway or street is presumed to carry title to the center of that roadway. . .”); Town of Moorcroft v. Lang, 779 P.2d 1180 (Wyoming 1989) (“[w]hen the developer sells an abutting lot, the common law presumes he intended to convey not only the lot specifically described in the deed but also to the middle of the adjoining street”); See also, Standard Oil Co. v. Milner, 152 So.2d 431 (Ala. 1962) (stating that the centerline presumption applies “on the theory that the grantor did not intend to retain a narrow strip of land which could hardly be of use or value except to the owner of the adjoining land”). The presumption typically arises only after the road or highway has been vacated or abandoned by the municipality. In such situations, a question often arises as to who now owns the surface estate where the public road or highway was formerly located. The centerline presumption is therefore used to ascertain who owns that narrow strip of land after it is no longer being utilized as a public road or highway. As Pennsylvania Supreme Court in Rahn correctly observed:

“[I]f the streets were to be vacated, of what value would they be to the original grantors. . . ? A long strip of ground fifty or one hundred feet wide and perhaps several miles in length, without any access to it except at each end, is a description of property which it is not likely either party ever contemplated. . .”

Rahn, 378 Pa. at _______. The centerline presumption, however, typically does not come into play while the roadway is still active: the roadway itself is a public easement and the abutting landowner merely has a reversionary future interest in the surface that becomes exclusive and possessory only if the roadway is subsequently abandoned.

Back to Great Northern Properties. On appeal, GNP argued that the trial court and Extraction were using the centerline presumption in a way that was never contemplated: to immediately convey the oil and gas estate underlying the roadway to the abutting landowner while the roadway was still being used. According to GNP, the centerline presumption has never been recognized or applied as an immediate conveyance. Since the centerline presumption was developed to address ownership of the surface after the roadway is abandoned or vacated, it makes no sense to immediately apply that presumption to oil and gas. GNP noted that the policy behind the centerline presumption is simply not applicable to the underlying oil and gas: while the narrow strip of land formerly used as a roadway may not have any value to the original grantor, the oil and gas estate can and does have significant value to the original grantor irrespective of the surface. This is especially true in the era of horizontal drilling. In other words, the centerline presumption was created and adopted to address the ownership of a narrow strip of land that is essentially useless to the original grantor. The same cannot be said of the oil and gas estate underlying the roadway.

GNP further noted that the centerline presumption does not operate to immediately convey any possessory interest in the roadway to the abutting landowner. That possessory interest in and to the “center” of the roadway only arises in the future if the roadway is abandoned. Why should the oil and gas estate be immediately conveyed to the abutting landowner when the same is not true for the land under the roadway? GNP argued that trial court wrongfully accelerated the timing of the centerline presumption to immediately convey the oil and gas estate under the roadway. That is wholly inconsistent with how the centerline presumption typically operates. As such, GNP argued that, as a matter of public policy, the centerline presumption simply should not apply to oil and gas interests.

In a complicated and controversial opinion, the Court of Appeals affirmed the trial court’s ruling and held that, when applicable, the centerline presumption applies to all property interests beneath the purported roadway. As such, the Court of Appeals squarely rejected GNP’s argument that the presumption should only apply to the surface estate. The Court of Appeals then articulated a “new” four-part test governing when and how the centerline presumption is triggered. In order for the centerline presumption to apply, the Court of Appeals ruled that these four conditions must be satisfied:

- the grantor conveys ownership of a parcel of land abutting a right-of-way;

- at the time of the conveyance, the grantor owed the fee underlying the right-of-way;

- the grantor conveys away all the property they own abutting the right-of-way; and

- no contrary intent appears on the face of the conveyance.

The Court of Appeals also addressed the “timing” issue. In a controversial move, the Court of Appeals opined that “[B]ecause all of these conditions must be satisfied before the centerline presumption applies, we further clarify that title to the centerline . . . passes to the abutting property owner once the last of these conditions is satisfied.” The Court of Appeals then concluded that all four of these conditions were satisfied in 1975. As such, title to the oil and gas estate to the center of Eleventh Street automatically passed to the abutting landowners at that time.

Given the Court of Appeal’s expansion of the centerline presumption, GNP filed a writ of certiorari with the Colorado Supreme Court on October 22, 2022. The Colorado Supreme Court granted the petition on March 20, 2023 and oral argument on GNP’s appeal was heard on December 12, 2023. As of this publication, no ruling has been issued by the Colorado Supreme Court.

It is submitted that the opinion issued by the Court of Appeals does raise more questions than it answered. The new timing element suggested by the Court of Appeals could create a headache for title examiners. Putting aside the question of whether the centerline presumption should even apply to oil and gas interests, under the Court of Appeals formula, the conveyance of the oil and gas under a roadway could occur decades after the initial conveyance. For example, returning to our Reese Drive hypothetical, let’s assume that XYZ Development sold nine of the abutting lots in 1984 but retained ownership of Lot 10 until 2020. According to the Court of Appeals opinion, all of the oil and gas underlying Reese Drive would suddenly and automatically transfer to the individual abutting lot owners in 2020. The opinion fails to adequately address who owned the oil and gas under Reese Drive between 1984 and 2020. That uncertainty as to who owned the oil and gas during this time will certainly discourage and delay oil and gas development. In addition, the Court of Appeals opinion does not explain how the oil and gas under a roadway suddenly has no value once the original grantor conveys his last abutting parcel. The advent of horizontal drilling undermines the Court of Appeal’s logic: the oil and gas formations have value regardless of whether the grantor retains ownership of the abutting surface parcels. As such, the notion that the oil and gas estate under the roadway will magically have no value once the last abutting parcel is conveyed is nonsensical. The author submits that the most pragmatic and reasonable approach is the framework advocated by GNP in the first place: the centerline presumption should simply not apply to the oil and gas interests under roadways.

If you have questions about the ownership of oil and gas under a roadway or highway, please contact Robert J. Burnett at 412-288-2221 or rburnett@hh-law.com.

About Us

Oil and gas development can present unique and complex issues that can be intimidating and challenging. At Houston Harbaugh, P.C., our oil and gas practice is dedicated to protecting the interests of landowners and royalty owners. From new lease negotiations to title disputes to royalty litigation, we can help. Whether you have two acres in Washington County or 5,000 acres in Lycoming County, our dedication and commitment remains the same.

We Represent Landowners in All Aspects of Oil and Gas Law

The oil and gas attorneys at Houston Harbaugh have broad experience in a wide array of oil and gas matters, and they have made it their mission to protect and preserve the landowner’s interests in matters that include:

- New lease negotiations

- Pipeline right-of-way negotiations

- Surface access agreements

- Royalty audits

- Tax and estate planning

- Lease expiration claims

- Curative title litigation

- Water contamination claims

Robert Burnett - Practice Chair

Robert’s practice is exclusively devoted to the representation of landowners and royalty owners in oil and gas matters. Robert is the Chair of the Houston Harbaugh’s Oil & Gas Practice Group and represents landowners and royalty owners in a wide array of oil and gas matters throughout the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Robert assists landowners and royalty owners in the negotiation of new oil and gas leases as well as modifications to existing leases. Robert also negotiates surface use agreements and pipeline right-of-way agreements on behalf of landowners. Robert also advises and counsels clients on complex lease development and expiration issues, including the impact and effect of delay rental and shut-in clauses, as well as the implied covenants to develop and market oil and gas. Robert also represents landowners and royalty owners in disputes arising out of the calculation of production royalties and the deduction of post-production costs. Robert also assists landowners with oil and gas title issues and develops strategies to resolve and cure such title deficiencies. Robert also advises clients on the interplay between oil and gas leases and solar leases and assists clients throughout Pennsylvania in negotiating solar leases.

Brendan A. O'Donnell

Brendan O’Donnell is a highly qualified and experienced attorney in the Oil and Gas Law practice. He also practices in our Environmental and Energy Practice. Brendan represents landowners and royalty owners in a wide variety of matters, including litigation and trial work, and in the preparation and negotiation of:

- Leases

- Pipeline right of way agreements

- Surface use agreements

- Oil, gas and mineral conveyances